I love Asolo because it is beautiful and peaceful, a village of lace and poetry; because it is not far from Venice, which I adore; because it is home to good friends whom I love; because it is between Mounts Grappa and Montello….

This will be the nursery of my old age, and here I wish to be buried. Indeed, remember that, and if the moment comes, say so.

Eleonora Duse

1.

Arrigo Minerbi (1881-1960)

Bust

This sculpture was donated to the new Duse Theatre by Lyda Borrelli Cini in 1934.

The bust was exhibited at the 1932 Venice Biennale.

1932 – Marble

2.

Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904)

Portrait

This piece was a gift from Duse to Count Giuseppe Primoli (1851-1927), who was a close friend of the actress

1885 – Charcoal, watercolour, chalk, paper

3.

Eveline von Maydell (1890-1962)

Silhouette

Eleonora Duse portrayed during her last American tour

1923 – Paper with bonding

4.

Franz von Lenbach (attributed)

Medallion which reproduces the portrait of Duse and little Marion Lenbach, the painter’s daughter.

The original is possibly a photographic portrait taken in Munich at Karl Hahn’s studio

1897 – Lithographic film copy, cardboard

5.

Arnold Genthe (1869-1942)

Portrait

The last photograph taken during Duse’s tour in North America.

1923 – Albumen print, paper

6.

Frederick von Rieger (1903-1987)

Portrait

This painting portrays the actress in the staging of Ibsen’s Rosmersholm. It was donated by the author to the Museum in 1976.

1928 – Oil on panel

7.

Ilya Yefimovich Repin (1844-1930)

Portrait

Engraving from a charcoal sketch

1893 – Dry point engraving

8.

Walter Clark (1859-1935)

Portrait

It seems that this portrait was a gift from the painter to the Head of the Italian Government, and from him to the town.

There is a terracotta portrait of Duse in the collection by the same artist

1933 – Oil on canvas

Franz von Lenbach – an artist, a friend

Franz von Lenbach (1836 – 1904), who received his training at the Munich Academy, dedicated his studies to the art of the old Renaissance masters from Italy.

He spent an extended period in Rome and even established the ‘Red Studio’ in Palazzo Borghese, which Gabriele D’Annunzio referred to in the pages of Il Fuoco.

He was a talented portrait artist known for the emotional depth in his paintings.

He had many esteemed clients, including the Austrian royal family and prominent members of European high society.

Eleonora Duse and Lenbach must have had a close relationship, evidenced by his numerous portraits of her, capturing the expressiveness of her face, especially in the theatre. One of the most striking portraits is the intense portrait of Asolo, which captures both her beauty and her talent as an actress.

In the Asolan collection, in addition to the painter’s family photo, there is a small sketch in a medallion depicting Eleonora with little Marion Lenbach, whom the painter loved to portray, always infusing her image with a hint of mysterious restlessness.

1.

La Mura

Eleonora Duse first visited Asolo in 1892 as the guest of the American Katherine De Kay Bronson (1838-1901). In a letter to Isabella Stewart Gardner, Bronson described how the actress had spent a few days in Asolo at her house, which was known as ‘La Mura’, praising its simplicity. The living room at La Mura inspired the actress to come up with her vision of the ideal home, made of bare stone walls; without carpets or curtains; with a bed of maize leaves and a thin woollen mattress, as peasants often had in their homes.

The only touch of refinement was brocade fabric to soften the bed, as she wrote in some of her letters.

Duse certainly felt the fondness of Bronson, who described her as ‘a soul exhausted by the struggle for life, dead tired of deceitfulness and lies and even the applause of crowds’.

Her memories of the time spent at La Mura, which she saw as a temporary yet peaceful refuge, prompted Duse to return in 1920. However, the house, no longer lived in and cared for by its owners, proved to be uncomfortable, so she decided to leave ahead of schedule, but not before restoring the rose garden.

2.

Casa Casale

Duse met Pietro and Lucia Casale in Venice in 1912. Pietro Casale (1865-1928) was a language professor and excellent musician, and Lucia Occioni Bonaffons (1866-1933) was the director of the lace school at their home in San Tomà, Venice.

The Casale family moved to a small house in Via Belvedere in Asolo that same year, hosting the actress occasionally, giving her a bedroom and a small living room decorated in Venetian style.

For her part, it was Duse who encouraged Lucia Casale to found the lace school called Antico Ricamo Italiano in Asolo in 1919, taking over and renovating the former Scuola di Merletti Browning.

Day or night, Duse loved to stroll in the Casale family garden, which was connected to a tower within the old city walls, and she never tired of listening to the harmonium played by Pietro.

Duse soon told Lucia that she wished to find a house in Asolo so that she could enjoy the company of her friends while remaining more independent.

In 1919, Lucia put her in contact with Mr Cantoni, an engineer and the administrator of the neighbouring house, which would later become Casa Duse, owned by Mrs Miller Morrison of Edinburgh.

3.

Albergo Alla Torre

Duse stayed at this hotel in Via Marconi, Asolo, next to the local weaver’s workshop and close to Casa La Mura, in the spring of 1913 and on a few other brief occasions.

A guest book with guest signatures testifies to her presence.

4.

Albergo Al Sole

Duse’s fleeting stays at this hotel began in June 1920.

She enjoyed its homey atmosphere, occasionally staying here during the years in which Casa Morrison was being renovated. The hotel was run by Giulio Favero and his sisters. The Favero family provided every possible comfort for Duse, always ensuring she got her favourite room and preparing the dishes she loved most.

The actress wrote numerous telegrams to Mr Favero: to ensure her luggage was on its way from one destination to another; to ask him to send her the mail; to arrange transport from the station to the city, or to ask her dear Teresa to check on the house.

Today the hotel is a charming residence, and room 202, named after the actress, has been faithfully restored. It still safeguards some of the letters that Duse wrote to the Favero family.

5.

Casa Duse

In September 1919, Lucia Casale put Duse in touch with Mr Cantoni, who was an engineer and the administrator of a house owned by Mrs Miller Morrison of Edinburgh. Duse liked the house because it was sunny and bright, and because she could enjoy a sweeping view of the plains and the Grappa massif from its windows. She especially liked the attic, then used as a granary, which she asked to be converted to a living space Duse decided to rent the house for two years and, although she stayed there only a few times, she was constantly thinking of the work she wanted to complete in order to live there permanently.

However, in March 1920, she suddenly terminated the lease, realising that it would be impossible for her to return to Asolo that year. In May she tried to go back on that decision, but in the meantime the house had been rented to a family from Cremona, whose daughter had lost her fiancé on Mount Grappa during the war. Duse was determined to leave her trunks at Casa Morrison anyway, and she signed another lease that began on 15 October 1920. At the end of October, she returned to the house and stayed there for a few days, ordering further work to be done and asking her friends in the Casale family to oversee the choice of silk fabric for the upholstery.

This was followed by sporadic visits in July 1921, August 1922 and May 1923, with the aim of seeing the work being done and arranging for future modifications, such as the construction of an access gate to the courtyard and a fountain.

Around that time, she also asked a carpenter by the name of Mr Cadonà to install a lamp with a light blue glass shade to illuminate the niche on the exterior wall of the house which held a small fresco of the Virgin Mary. The precious lamp was constantly on her mind: the night before she departed for the United States, she made sure to leave one last bit of advice on how to properly care for it.

The house, which was never permanently lived in due to the actress’s sudden death, was bought by her daughter Enrichetta, who lived there for some time with her family. In 1934, just before she moved to England, Enrichetta decided to donate it to the Acelum Society of Asolo. The president of the group was the provost Don Angelo Brugnoli, who in turn gave the house to Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, heir to the famous Irish brewery.

6.

The memorial plaque

On the one-year anniversary of the actress’s death, a plaque bearing an inscription by Gabriele d’Annunzio was placed on the facade of Casa Duse:

To Eleonora Duse,

last-born daughter of Saint Mark

a melodious apparition

of the creator’s affliction

and sovereign goodness,

this home

the peaceful repose of the great actress

on the first anniversary of her death

Asolo hereby consecrates

21 April 1925

The event was attended by many distinguished people, including an official speech by Tommaso Gallarati Scotti, author of Niente and Così Sia, the last play acted in; Ciro Galvani, an actor from her company; and actress Tatiana Pavlowa.

7.

Museo civico

In 1933, Eleonora Duse’s daughter was soon to move permanently to Cambridge, where her husband Edward Bullogh was teaching. So, she donated the objects, clothes, furnishings, and iconographic and documentary materials that had belonged to her mother and were present in the Asolo house to the Italian State, with the caveat that they would be kept at the Civic Museum. The donation, supported by Maestro Gian Francesco Malipiero, who also oversaw the arrangement of the new museum room, was made official in April 1934.

8.

Teatro Duse

On 2 May 1932, following a major restoration, the new Municipal Theatre named after Eleonora Duse was solemnly inaugurated in the Castle (‘…by the unanimous will of local citizens, it was decided to name it after Eleonora Duse…who has chosen to sleep her last sleep here in the small cemetery of Asolo’).

In 1827, the theatre had hosted the company of Luigi Duse, Eleonora’s grandfather, but the great actress never performed there.

The new theatre was installed in the 16th-century hall, building a large loggia with 11 boxes. The coffered ceiling was decorated with paintings, while restored original frescoes could be admired on the walls. An auditorium that could hold 294 people, a stage, and a space for the orchestra in an acoustic shell completed the structure.

The cast of Eleonora Duse’s hand is displayed in a case in the atrium. It was made by Miss Etta Macy (called the ‘Poor Clare from overseas’ by d’Annunzio) and was donated to the Municipality by Lucia Casale. A bust by Arrigo Minerbi, donated by silent film star Lyda Borrelli Cini, was added in 1934.

The opening of the theatre was widely reported in the national press.

The picturesque natural backdrop formed by the castle, the raised courtyard garden, and Reata Tower were particularly well suited to outdoor plays and, from August 1935 onwards, this natural setting hosted productions of D’Annunzio’s plays for the most part, such as The Dead City, Più che l’Amore, The Daughter of Iorio, and La Fiaccola Sotto il Moggio.

9.

Piazzetta Duse

The work done on the Castle to accommodate the new theatre involved the demolition of a cluster of houses against the north wall of the structure, thus creating space for a small square that was named after Eleonora Duse in 1934.

10.

Cimitero di Sant’Anna

Completed in 1887, the oldest part of this cemetery houses the chapels and tombstones of prominent local figures. Eleonora Duse was buried here in 1924. Speaking to Marco Praga during a meeting in Asolo in 1919, the actress stated:

I love Asolo because it is beautiful and peaceful, a village of lace and poetry; because it is not far from Venice, which I adore; because it is home to good friends whom I love; because it is between Mounts Grappa and Montello….

This will be the nursery of my old age, and here I wish to be buried. Indeed, remember that, and if the moment comes, say so

Ada Negri recalled that the small, humble Sant’Anna Cemetery was considered by Duse to be ‘the most intimate and solemn of cemeteries’.

Enlarged in 1927 (after the presence of Duse’s tomb made it a pilgrimage site for her loyal fans), in 1928 the cemetery was entrusted to the attentive care of the Capuchin Friars, who became the owners of the adjoining convent and church dedicated to Saint Anne.

Numerous famous people have visited the grave of the great actress over the years, including: Gabriele d’Annunzio; his architect and personal secretary, Giancarlo Maroni; impresario and theatre producer Morris Gest (1875-1942); art historian Bernard Berenson (1865-1959); actor Memo Benassi (1886-1957); actress Vivien Leigh (Scarlett O’Hara) with her husband Laurence Olivier; actress Ingrid Bergman; and Duse’s niece, Sister Mary.

1.

Photograph from The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas

Photograph of Eleonora Duse as Marguerite Gautier

1882 – Gelatin silver print, paper

2.

Photographs of Eleonora Duse in Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Francesca da Rimini

The photos are precious evidence of the stage and set that d’Annunzio had built

1901 – Gelatin silver print, paper

3.

Portrait of Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863-1938)

This photograph was donated by the poet to the Mutilati di Asolo

1921 – Photographic reproduction

4.

Photographs to study Scandinavian settings

The first one is a photo of the Britannia (1893) and was probably used as part of the set for The Lady from the Sea

The second one is a print with a landscape with trees on the outskirts of Graested, Denmark

Attributed to the artist Holm Axel (1861-1935).

Late 19th century and 1893 – Gelatin silver print and etching

5.

Photograph of Francesca’s house in Ravenna

This photograph belonged to the actress, probably a memento linked to her famous performance

Late 19th – early 20th century – Albumen print, paper

6.

Portrait of Henrik Ibsen by Nordhagen Johan (1856- 1956)

1904 – Dry point, etching, paper

7.

Cast of Eleonora Duse’s right hand

This cast was made by Etta Macy (1854-1927), who d’Annunzio called ‘the Poor Clare from overseas’, and was donated by Lucia Casale to the City for the inauguration of the new E. Duse Theatre

1932 – Clay

8.

Bust of Eleonora Duse by Walter Clark (1859-1935)

Donated to the Museum in 1938.

The museum also has an oil portrait by the same artist, in which he remains faithful to the same iconography

Late 19th – early 20th century – Terracotta

9.

VView of Stratford upon Avon, the house where Shakespeare was born and the interior of the house.

Three photographs belonging to Duse depicting the place where the famous English playwright was born

Late 19th – early 20th century – Albumen print, paper

10.

Portrait of William Shakespeare attributed to Charles William Sherborn (1831 – 1912)

This portrait seems to have always been with the actress on her travels

1876 – Etching, paper

11.

Asolo-made caned armchair

1900-1925 ca. – Walnut wood and straw

12.

Sewing box with interwoven cotton ribbon

Probably a prop

Late 19th century – Wood

13.

Small table with a drawer and sideboard

Seen in a photo of the Asolo house, though it probably was from the house in Florence

19th; 17th century – Wood

14.

Sewing set, embroidery frame, knitting needles

These items are generally believed to have been used in the performance of Ibsen’s Ghosts

Late 19th – early 20th century – Silver, lathe-turned wood and modano lace with embroidery, wood and metal

15.

Carpet

Mid-19th – early 20th century – Wool woven on a handloom

16.

Chest and lectern

These items are believed to have been part of the set props used for the production of Francesca da Rimini (1901)

Mid/end 19th – early 20th century – Wood and iron, wood

17.

Theatrical texts by Shakespeare, Dumas, Ibsen and others

These texts were part of the library that belonged to the actress, kept at Casa dell’Arco

18.

Flower vase

Said to have been given to Duse by D’Annunzio. The mark on the bottom of the vase makes it possible to identify it as the work of the famous designer, goldsmith and glassmaker René-Jules Lalique (1860-1945), who started to produce jewellery and crystal objects inspired by Art Nouveau in 1885

Late 19th – early 20th century – Painting on crystal

19.

Large glass cup

This cup is part of a set of 22 antique Murano glass pieces which were treasured by the actress

19th – early 20th century – Glass

20.

Antique Murano glass items

Chalices, vases, bottles, cups, etc. Some items are believed to be aerosol instruments

Late 19th century – Glass

1.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Sketch for Act I of The Lady from the Sea by Ibsen

On the verso of the sketch, handwritten notes by Duse with notes to the set designer

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

2.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, Act I

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

3.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Sketch for Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, Act II

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

4.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Sketch for Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, Act III

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

5.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, Act III

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

6.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Sketch for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Acts I and III

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

7.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Acts I and III

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

8.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Sketch for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Act II

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

9.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Act II

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

10.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Act IV

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

11.

Natalja Goncarova (1881 – 1962) – attributed

Model for Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman, Act IV, last scene

1900-1925 ca. – cardstock, tempera painting

1921, back on stage

In 1921, for her grand return to the stage, Eleonora Duse chose to collaborate with the accomplished Russian artist Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962).

A very talented artist with a notable non-conformist temperament, Goncharova accepted Duse’s request, working for free with full availability and passion. The two women corresponded frequently and in detail through letters, telegrams and comments on the back of the sketches, evidence of their dedication to their work and their mutual respect.

The performance of Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea on 5 May 1921 in Turin was a triumph and Goncharova was also involved in the sets for Ibsen’s play John Gabriel Borkman. Although work was well advanced, the play was never staged.

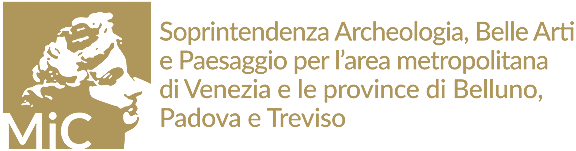

1.

Guerlain Veritable Eau de Cologne

Two bottles of the perfume used by Eleonora Duse

2.

Two of the seven unpublished books on Eleonora Duse ordered by Katherine Onslow

7 typescript books with photographs of the actress and reproductions of drawings (unpublished).

Pre-1926 – Typewritten on paper

3.

Small knitted purse with fringe

Used to hold coins, with a metal clasp on which the inscription Dèposè France is visible

Late 19th – early 20th century – Cotton with silver glass bead inserts

4.

Case with a small painting

The English cottage portrayed is probably Shakespeare’s house. 1900-1925 ca. – Oil on cardboard

5.

Antique filigree necklace

Kept in an antique case, probably a gift given during one of her tours in Russia.

Early 18th – late 19th century – Gold filigree, leather and gold embossing

6.

Crystal paperweight with two 5-franc coins

Donated by A. Lugnè Poe (1869-1940) of the Paris Opera House to celebrate the actress’s participation in the performance of the Russian drama The Lower Depths by Maxim Gorky. Duse acted in Italian and asked for only 10 francs, the smallest actor’s fee there was. The inscription on the back reads Le cachet de Eleonora Duse.

1905 – Crystal, engraving, grinding

7.

Yellow gold ring with a pearl

Given to the Museum by Maud Onslow, Katherine’s sister, a close friend of the actress and supporter of her last US tour

Late 19th – early 20th century – Gold and pearl

8.

Ribbon with a dedicatory inscription commemorating the first performance of Francesca da Rimini

1901 – Silk and print

9.

Notebook with a parchment cover

Containing excerpts from Francesca da Rimini in the actress’s handwriting

1901 – Paper, ink, parchment

10.

Set of 15 business cards

1900-1925 ca. – Cardboard and embossing

A perfume for Eleonora: Guerlain veritable eau de cologne

Eau de Cologne Impèriale was created in 1853 for Empress Eugènie, wife of Napoleon III, and was Guerlain’s first Eau de Cologne. The fragrance is a floral citrus. The empress enjoyed the fragrance exclusively before making it available to the general public. Its creator was bestowed with the title of ‘Perfumer of Her Majesty,’ becoming the perfumer of choice for royalty and nobility.

Guerlain created not only the perfume but also the bottle decorated with 69 bees. The bee would later become the symbol of the house. The label is adorned with the symbol of the empire with Napoleon’s chosen coat of arms, featuring the eagle, the crown and the sceptre – the imperial symbol.

The cologne is still sold in bottles with the original designs, either in white or hand-painted gold bee designs. Only a few changes have been made to the content, with a simple,100% natural formula.

The memory and devotion of friend Katherine Onslow

The seven volumes by Katherine Onslow collect news and articles from Duse’s debut in St. Petersburg in 1891 to her last tour in the United States. The final two supplements featuring a captivating collection of photographs are surely worth perusing.

The rich noblewoman was a great admirer of the artist; she provided her with financial support that enabled Duse to resume acting in the 1920s, and also accompanied the actress during her last American tour.

In 1919, Katherine wrote to Enrichetta about her plans to donate her vast collection of articles to the British Museum in memory of the actress. The presence of the books in Asolo can be attributed to her cousins, Lord and Lady Iveagh, who were benevolent enough to purchase the Duse residence.

Shortly after Eleonora’s death, Katherine discovered she was seriously ill and passed away in December 1926. Miss Maud, Katherine’s sister, donated the pearl ring that belonged to the celebrated actress to the Civic Museum in 1938.

1.

Black evening gown with a train

Long black dress with a train, made of silk and tulle embroidered with small beads, jet beads and multifaceted glass beads.

Paris, Maison Redfern

Late 19th – early 20th cen.

2.

Black satin shoes

These court shoes were probably worn during Marco Praga’s play La Porta Chiusa, although a recent hypothesis connects these shoes to the staging of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s The Dead City. They feature a pointed toe, a black satin upper, dark leather lining and a leather sole. The inside of the sole is stamped with the shoemaker’s trademark.

Made by Caporale Donato, Milan

Early 20th century – Silk, satin, and leather

3.

Aquamarine dress

Dress in lustrous blue-green aquamarine silk taffeta, embellished by light blue silk velvet details.

Paris, Atelier of Charles Worth

Late 19th – early 20th cen.

4.

Brown wool costume

Generally attributed to the play Così Sia (1922) by Tommaso Gallarati Scotti. This straight-cut frock features long kimono sleeves and a pointed hood, complemented by a rectangular bag in the same fabric as the garment.

Italy

C. 1900-1925 – Woollen cloth

5.

Brown suede shoes with a strap

Worn for the production of Gallarati Scotti’s Così Sia, staged on 12 January 1922. Court shoes with a strap and rounded toe. The upper features light-coloured edging and openwork on the strap. Leather lining; burgundy leather sole stamped with the shoemaker’s trademark.

Made by Calzoleria Mebuloni, Milan

C. 1900-1925 – Suede and leather

6.

Yellow wool shawl

Generally considered to have been worn during the first staging of Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House in 1891 in Turin, this shawl consists of two triangular halves made from a single shawl with fringe at the sides.

Italy

Late 19th century – Woollen cloth

7.

Light blue tunic and purple wool skirt

This costume was probably worn for Ibsen’s Ghosts, a play which Duse brought to the stage on 18 October 1922. It consists of a loose-fitting light blue cotton blouse with an asymmetrical hem, two pleats on each shoulder, long sleeves, a V-neck and a front placket with four mother-of-pearl buttons. The roomy purple woollen cloth skirt is gathered and held in place by the waistband, which is fastened with press studs and metal hooks. The hem is trimmed by ribbon containing lead weights.

Italy

1922 – Cotton, woollen cloth

8.

Blue silk umbrella

This umbrella was part of the stage costume used for Goldoni’s The Mistress of the Inn, and thus worn by Duse at the beginning of her career. In light blue silk with a striped border in ivory, light blue and yellow, set onto an eight-segment gilded metal frame, it features a metal ferrule and a sculpted ivory handle.

Italy

Late 19th – early 20th cen. – Silk, taffeta, ivory handle

9.

Green velvet dress

This dress is generally traced back to Gabriele d’Annunzio’s play The Dream of a Spring Morning staged in Paris in 1897. With a princess cut, it forms a sort of sleeveless tunic that’s open at the sides, defined by a V-neck decorated with metallic passementerie and chenille. The gathers at the shoulders and waistline are marked by the same trimmings as the neckline.

Paris

Late 19th century – Cotton, velvet, metallic thread and silk thread

10.

Shoes in gold-coated satin Stage costume for the play The Lady from the Sea

Court shoes with a pointed toe. The upper is made of gold-coated satin which is lined in leather on the inside. The leather sole is stamped with the shoemaker’s trademark.

Made by Calzoleria Mebuloni, Milan

C. 1900-1925 – Silk, satin, metallic coating

11.

Green jacket

Form-fitting jacket in green velvet with black embroidery, a band collar, gigot sleeves, flounces, cuffs in black Chantilly-type lace. Green quilted silk lining. Placket with black metal hooks.

Italy

1885 – Silk, velvet, embroidery, and cotton thread; machine sewn

12.

Pink satin shoes with a gold coating

Court shoes with a pointed toe. The upper is made of gold-printed satin which is lined in leather on the inside. The leather sole is stamped with the shoemaker’s trademark.

Made by Calzoleria Caporale Donato, Milan

Early 20th century – Silk, fabric, detailing

13.

Silk scarf

Generally considered to have been worn during the staging of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, the square shape of this silk scarf is accentuated by a paisley motif in yellow, orange, green and white on a green background.

Italy

Late 19th century – Silk

14.

Black parasol

One of the stage props used for The Lady from the Sea, the canopy of this parasol is formed by beige silk taffeta that has been covered in black Chantilly bobbin lace. The sculpted ivory handle and ferrule feature undulating forms decorated by bead-like detailing. A tassel in beige silk thread is tied to the handle.

Paris

Late 19th – early 20th century – Silk, taffeta, lace, ivory handle

15.

Fur coat

Traditionally considered to have once been owned by Duse, this fur was bought by actress Valentina Cortese and reinterpreted by fashion designer Maurizio Galante. It consists of a silk and lace outer shell with the sleeves, lining and edging in ermine fur, embellished with silk velvet flowers on the neckline. France

Late 19th century – Silk, lace, ermine fur

Evening gown with a train

Made of black silk fabric, the outer shell of the dress is made of tulle in the same colour, embroidered with jet beads and smaller beads forming a refined arabesque motif. Draped over the shoulders and chest, a layer of tulle forms a sort of wide flounce with circular decorations in larger-size multifaceted pearls. The jewel-neck, fitted bodice, supported by boning, is closed at the back via metal hooks. The long sleeves are fuller at the top, narrowing to contour the forearm with a high cuff, secured by press studs. The skirt drops to the floor where it opens like the corolla of a flower, extending into a train at the back. The petticoat is trimmed along the hem by a wide silk border worked into loose folds.

The dress is a creation of Maison Redfern in Paris, a couturier to celebrities and the upper echelons of nobility in Europe.

John Redfern was also the tailor of the Princess of Wales and the Empress of Russia.

Aquamarine dress

This dress has traditionally been identified as one of those worn in 1909 on stage by Eleonora Duse as Ellida, the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea.

It was restored in 2003, a complex effort that involved the cleaning and reconstruction of the torn fabric. However, it managed to bring back the identity and substantial integrity of the garment.

The placket is adorned by six painted wooden buttons in the shape of flowers. It is open at the front, fitted by darts at the front and back, and decorated along the edges by silk ruffles.

The dress was made by the House of Worth (Paris), the most prestigious European fashion maison of the time. Duse was a repeat customer of Worth, which made garments for her to wear both in real life and on stage.

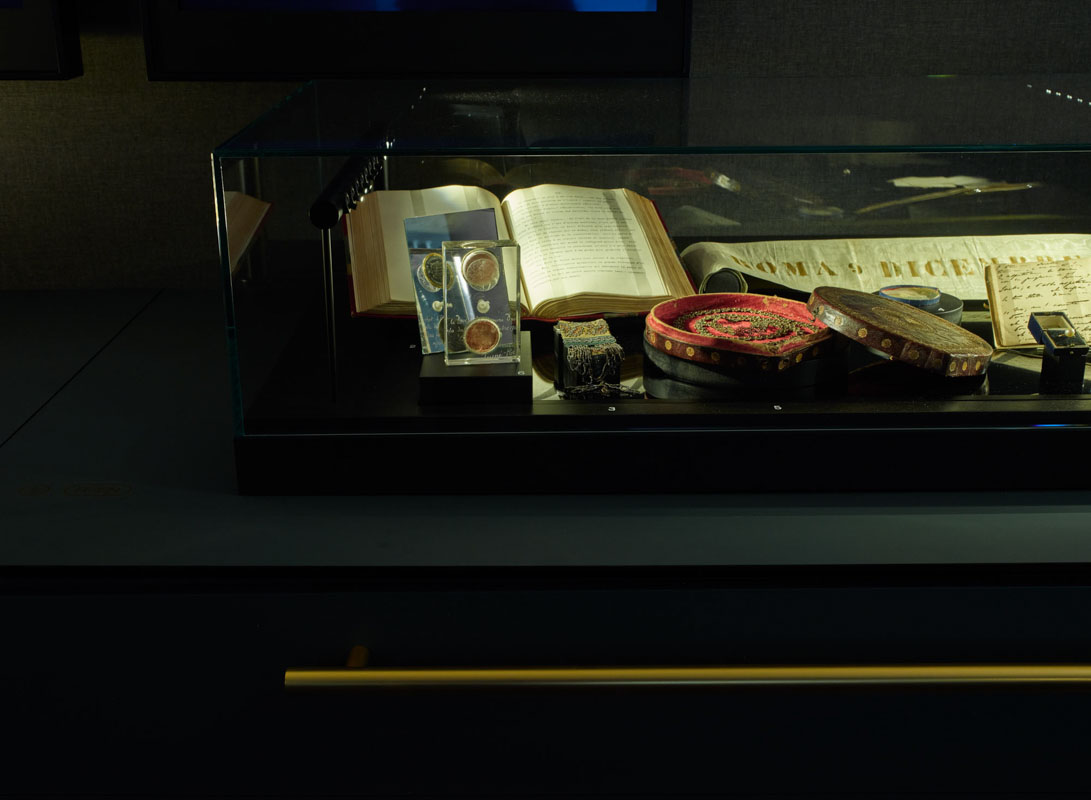

You have to be out in the world; it isn’t enough to write beautiful things. You must go out and talk to people, you must explain and defend your work; it takes action, you must act! And to take action, theatre is indeed a first-rate medium…

One Sunday in May, in the immense arena in the ancient amphitheatre under the open sky, I have been Juliet before a popular multitude that had breathed in the legend of love and death. No quiver from the most vibrating audiences, no applause, no triumph has ever meant the same to me as the fullness and the intoxication of that great hour… How I spoke of the nightingale and the lark! I had heard them a thousand times in the countryside. I knew all their songs of the woods, the meadows, the clouds. I had them in my ears, alive and wild. Every word, as it left my lips, seemed to have been steeped in the warmth of my blood… I had bought a great bunch of roses with my little savings in Piazza delle Erbe… The roses were my only ornament, I mingled them with my words, with my gestures, with each attitude of mine

Gabriele d’Annunzio, The Flame of Life

Acting? What a terrible word! If it only were a matter of acting; I feel that I have never known and will never know how to act! Those poor women in my plays have entered my heart and head to such an extent that while I endeavour to make them understood as best I can to those who listen to me, almost trying to comfort them, it is they who, ever so slowly, have ended up comforting me… not one woman—a thousand women I feel I have inside me…

Olga Signorelli, Eleonora Duse, Roma, 1955, p. 57, Letter to the Marquis d’Arcais

In art, emphasis is the easiest and most beaten path; sincerity and simplicity are atop the peak of the mountain, yet few manage to climb up there without wheezing

Part of the audience does not accept me as I would like to be accepted because I only do things in my own way, that is to say, as I feel them… It’s agreed that in certain circumstances you must raise your voice, fly off the handle and I, on the other hand, when the passion I express is violent, when my soul is struck by pleasure or pain, I often fall silent and speak softly on stage, almost in a whisper…

Olga Signorelli, Eleonora Duse, Roma, 1955, p. 44

Each of us must follow our own calling… I want to go back to work, I want to go back to work, I want to go back to work…

I will appear before the spectators with my tired old face full of wrinkles and my white hair… and I will try to bare my soul… if they like me even in this state, I’ll be happy and proud… if not, I will return to silence, but no tricks, no refinishing, no lies…

Olga Signorelli, Eleonora Duse, Roma, 1955, p. 170

(On journalists) It’s hard work and thankless too. That of answering those who turn up at my hotel and ask me hundreds of inappropriate questions, under the pretext that an actress belongs to the audience. It seems to me, on the other hand, that an actress should arrive fresh on the stage, without first showing the spectators what the toy that they will be entertained by is made of…

Olga Signorelli, Eleonora Duse, Roma, 1955, p. 113

(Her response, when invited to write about art) …it would be the same as explaining love. We’ve all borne that cross—we’ve all talked about it, and no one, absolutely no one has defined it completely. You love, how you love, and if you are an artist, how you feel.

Success, affiliations, and traditions above all, are worthless in art. There are many ways to love, and there are just as many manifestations of art. There is love that elevates, and there is love that absorbs your every will, every strength, every line of intelligence. In my opinion, that’s the truest, but certainly the most fatal… just as in art… which sometimes reveals itself to be the expression and expansion of a soul…

Giuseppe Boglione, L’arte della Duse, Roma, 1960, p.8

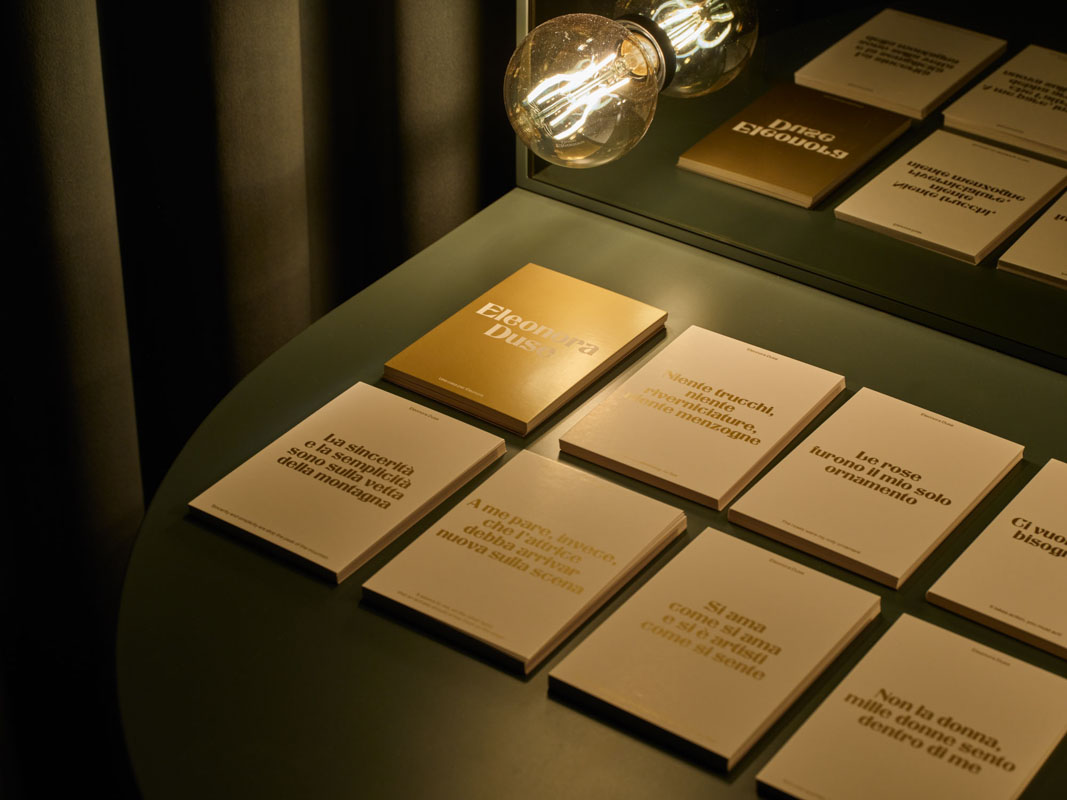

1.

Poster: American Poets’ Ambulances in Italy, 1917

Ambulance 86 was donated by the association in the name of the actress

1917 – Print with a handwritten dedication

2.

Two soldiers holding Volkoff’s portrait of Duse

The portrait is taken from a drawing made in 1893 by Alexandre Volkoff, who hosted the actress in his palace in Venice. The artist was instrumental in Duse’s theatrical début in Russia in 1891

1900-1925 ca. – Albumen

3.

Image of the Madonnina del Grappa

This statue was blessed by Patriarch Giuseppe Sarto (later Pope Pius X) in 1901 and the holy image became dear to fighters from Grappa.

Postcard

4.

Small sculpture by Enrico Toti (1882-1916)

Memento of the Roman soldier who, despite being disabled, was enlisted. Mortally wounded in the trenches, legend has it that he hurled his crutch at the enemy.

1900-1925 ca. – Bronze

5.

Case containing letters from Duse sent to Countess Bianca di Prampero

The case is said to have once belonged to d’Annunzio. The letters were written between 1916 and 1921

1900-1925 ca. – Silk

6.

Pair of ribbons

One with the colours of Rijeka and the other those of Italy

1900-1925 ca. – Silk and gros de Tours

7.

Glass and metal wedding favour

Containing keepsakes – a medal with an embossed bersagliere head and a badge – given to the actress by soldiers

1900-1925 ca. – Glass and metal

8.

Small vase with a picture of the Duchess of Palmela

Recalling the close friendship that bonded the actress with Maria Luisa de Sousa Holstein (1841-1909), an important personality in the Portuguese and European cultural scene, and also a sculptor and generous benefactor

Mid 19th – early 20th century – Glass

9.

Texts by various authors with handwritten inscriptions

These texts were part of the library that belonged to the actress, present at Casa dell’Arco

Echoes of the Great War

Far from the scenes, close to the tragedy

Eleonora Duse experienced the Great War as an Italian, an artist and a mother. She left the scene in 1909, and the war did not interfere with her career and tours. However, in that difficult period, she focused on her love for her country, her pursuit of freedom and the fragility of human life. The conflict caused her health problems and restlessness, leading to various moves.

She would always read newspapers to get the latest news, comfort friends with children fighting in the war, and write to soldiers to help them reconnect with their families.

The Museum preserves her correspondence with Countess Bianca di Prampero; she was her guest in her villa in Tavagnacco (UD) in 1917. She also involved her daughter Enrichetta, who lived in Cambridge, to ask for news about a family member of the Countess who was a prisoner of the English.

Duse was granted permission to visit the front. On 12 August 1917, she attended the opening of the ‘Soldier’s Theater’, created to uplift the spirits of the combatants and the wounded. While she did not participate in the plays, her presence in the audience brought a sense of maternal support and encouragement to the soldiers.

During the First World War, Duse limited herself to one artistic experience, which was in the realm of cinema. She starred in the film Cenere (Italy 1916), a cinematic adaptation of the novel of the same name by Grazia Deledda.

One of the souvenirs from the Great War is a figurine of Enrico Toti (1882-1916), an admirable example of military valour. In addition, there is a gift from soldiers and a photo of the Duchess of Palmela in a small glass vase. The actress had sold the pearls gifted to her by the Duchess to meet the economic needs of the war period.

From Eleonora’s library

Eleonora Duse’s collection of books includes several notable titles dedicated to the Great War, which were donated to her by the authors.

Autograph dedications from the authors highlight their deep admiration for her. These authors were a diverse group of intellectuals with various interests: the young poet and soldier Guido Fontana; the writers Giuseppe Prezzolini (1882-1982) and Piero Jahier (1884-1966), leading exponents of the Florentine magazine “La Voce”; the economist Antonio De Viti De Marco (1858-1943), whose wife Etta (1864-1939) was also in contact with Duse; the writer Térésah (Corinna Teresa Ubertis, 1874-1964), who created the Italian version of Ibsen’s drama La donna del mare, which brought the great actress back on stage on 5 May 1921 at the Teatro Balbo in Turin.

The project for a shelter: the ‘Libreria delle attrici’

In May 1914, before the outbreak of the Great War, Eleonora Duse founded the ‘Libreria delle Attrici’ (the actress’ library) in Rome. The project, which required an enormous economic and organisational effort, was very interesting despite its utopian ideals. Her desire was to provide a refined, elegant, protective environment full of cultural stimuli to young actresses and culturally elevate them by giving them an opportunity for social redemption. The initiative was met with derision by critics and the world of theatre. It ultimately failed as Italy entered World War I the following year.

The catastrophic adventure of the Libreria delle Attrici was the main reason for the dispersion of Duse’s vast library, completed during the war years.

Writing set

1900-1925 ca. – Silver

Travel tea set

Made by J. Demuth in Berlin, purchased on one of Duse’s tours in Berlin.

1900-1925 ca. – Silver, glass

Leather travel case with three square-section bottles

1900-1925 ca. – Leather and glass

Cartier case

With the initials ‘E.D.’ in the centre.

Late 19th century – Leather

Case for bottles

A gift from the actress Gabrielle Réjane (1856-1920), this case is believed to have belonged to Adrienne Lecouvreur (1692-1730), an 18th-century French actress

Early 18th – late 19th century – Oil on wood, glass

Cylindrical leather travel case with two triangular-section bottles.

Made by J. Demuth in Berlin

1900-1925 ca. – Leather and glass

Leather travel case with two square-section bottles.

The trademark is that of Franzi, an important luggage producer founded in Milan in the first half of the 19th century

1900-1925 ca. – Leather and glass

Copy of the Nike of Samothrace

A gift from the actors of the Comédie-Française troupe for Duse’s first Parisian tour, when the theatre was made available by the actress Sarah Bernhard (1844-1923).The gift was accompanied by a long list of signatures.

1897- Bronze with engraving

Letter that accompanied the Nike.

It is signed by 103 people, some of whom can also be found in the photograph of Duse among the Comédie Française troupe taken in Paris in 1897

1897 – Paper

On the bookcase: sculpture of Medusa’s head

This plaque was at the head of the bed in the house in Florence

Late 19th – early 20th century – Bronze

Les Contes du Vieux Japon box set by Hasegawa Takejirō (1853-1938)

Rare original edition of 18 books translated into French, with illustrated covers and wood-block prints inside

1889-1905 – Wood-block prints on crepe paper

La Duse books by Katherine Onslow

7 typescript books with photographs of the actress and reproductions of drawings (unpublished)

Pre-1926 – Typewritten on paper

Texts by various authors

These books were part of the library that belonged to the actress, present at Casa dell’Arco

Pinacoteque Hellenique album

Copies of photos of Greek monuments

Early 20th century – Cardstock, photographic paper

Butterfly specimen (Blue Morpho) in a small display case

It is believed to be a souvenir that the actress took with her after the 1885 or 1907 tour

Tabletop lectern

The reading surface is boxed when folded

Early 20th century- Mahogany wood

Portrait case

Made in the US, this case is generally accepted as having carried the portrait by Lenbach

Mid-19th – early 20th century – Wood, fabric lining

Scales

This item, the symbol of Duse’s zodiac sign (Libra), was placed in the bedroom and regarded as a lucky charm

1900-1925 ca. – Brass

21 antique Murano glass items

Chalices, vases, bottles, cups, etc. Some items are believed to be aerosol instruments

Late 19th century – Glass

Large glass cup

This cup is part of a set of 22 antique Murano glass pieces which were treasured by the actress

Early 19th – 20th century – Glass

Statuette

Gift from Ermete Zacconi for the actress’s return to the stage in 1921

1921 – Ivory

Copy of King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid

Copy of the canvas painting King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), made in 1884 and exhibited at the Tate Gallery in London. At the bottom left is an inscription by Arthur Symons, who translated Francesca da Rimini into English

1905 – Photolithography

Sideboard and table

Made in Tuscany, probably from the house in Florence

17th century – Walnut wood

Bookcase

Made in Tuscany, probably from the house in Florence

Mid-19th – early 20th century – Walnut wood

1.

Playbills of performances with actors from the Duse family

Late 19th century – Print

2.

Copy of The Two Comedians (drawing)

Luigi Duse dressed as Giacometto Spasemi, a costume which the actor designed and completed himself

Early 19th century – Lithograph

3.

Payment note

The last line indicates the payment for 8 evenings of performances by Duse when she was still a child

Late 19th century – Paper

4.

Portrait of a Woman By Alessandro Duse

The subject is generally identified as Eleonora Duse as a girl

1888 – Oil on cardstock

5.

Pocket watch that belonged to Duse’s father, Alessandro Duse

Mid-late 19th century – Silver with a white enamel dial

6.

Small case with photographic portrait of Duse’s mother, Angelica Cappelletto (1833-1875)

Late 19th century – Leather

7.

Red leather case with a photo of Alessandro Duse (1820-1892), the actress’s father

Late 19th century – Gelatin silver print, leather

8.

Vest that belonged to Duse’s grandfather Luigi early

19th century – Cotton and velvet

9.

Walking stick

That belonged to Duse’s father Alessandro, which was one of the objects the actress always took with her on tour

Mid-late 19th century – Bamboo and brass

Her origins and family

The first years in Chioggia

Eleonora Giulia Amalia Duse was born in Vigevano on October 3, 1858, while her parents were on tour. In early 1859, she and her family moved to Chioggia, her father’s hometown, where she spent much of her childhood.

As the daughter of artists, she started acting at the age of four, playing the role of Cosetta in a shortened version of Les Miserables. Her name appeared on the list of actresses in the Company led by her uncle Enrico Duse when she was in Chioggia in 1867.

The grandfather Luigi Duse, and Duse siblings’ company

Luigi (1792-1854), Eleonora’s grandfather, turned his passion for drama into his career. His family had been in Chioggia since the 16th century.

In 1823 he founded the Comica Compagnia Duse. He performed in Padua, Venice, Lombardy-Veneto and Dalmatia; in 1827, he was in Asolo. His repertoire included serious works, adaptations of Goldonian works, and farces. He created a new mask, Giacometo Spasemi, a jovial Venetian that gained popularity with the public and consecrated Luigi Duse and his son Giorgio in the drama industry.

After achieving a considerable fortune, Luigi Duse built the Day Theatre in Padua with a capacity of about a thousand people in 1834. After his death, his sons took over the theatre until it was sold in 1859.

The company, including Eleonora’s father Alessandro Vincenzo, was highly appreciated by the public, but it dissolved in 1874. The Duses continued to act in other companies.

Her father, Alessandro Vincenzo Duse

Alessandro Vincenzo (1822–1892) As a young man, he studied fine arts but soon quit to join his father’s company as a leading actor.

In the years following his wife Angelica Cappelletto’s death (1833-1875), he took a secondary position and followed his daughter Eleonora’s career. When Eleonora became famous, he retired from the theatre and moved to Venice with her help. There he resumed his passion for drawing and painting, although he always remained an amateur.

The museum holds some of his artwork, including drawings, studies, and an oil portrait of Eleonora dated 1888.